IWP has published “European President” ranking based on the result of expert survey.Several important components have been taken into account for ranking the candidates.

• The IWP has turned to experts in the field of European integration, profile journalists and Western experts familiar with the Ukrainian politics, to express their opinion about candidates. 80 completed questionnaires have been received;

• The IWP has analysed programs and election rhetoric, finding out whether the candidate understands that the European integration requires not a mere promise “to join the EU as early as tomorrow”, but a complex of reforms;

• The IWP has studied the candidate’s attitude towards European issues in the past;

• Finally, we have personally asked the candidates to answer a questionnaire, which contains 17 test, indicative questions.

The IWP has chosen 8 the most popular candidates out of 23 registered by the Central Election Commission — those, who, according to the results of social polls, at the time of the launch of the project, have a chance to overcome the so-called psychological barrier of 4%. This list includes Petro Poroshenko, Yulia Tymoshenko, Sergiy Tigipko, Mykhailo Dobkin, Petro Symonenko, Oleh Lyashko, Anatoliy Grytsenko and Olga Bogomolets.

For more details on the methodology of the survey, see full pdf-version of the publication.

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

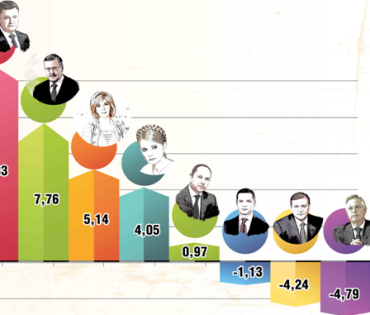

The expert survey and the IWP’s study have allowed to determine the leader of the ranking — it is Petro Poroshenko. The unanimity of support is telltale: 70 out of 80 experts included him in the triplet of those who merit the characteristic “European candidate”, while 54 of polled experts ranked him first.

9 experts have identified Anatoliy Grytsenko as the most European candidate; both Yulia Tymoshenko and Olga Bogomolets have been chosen as the most European by the same number (6) of experts. Three experts have put Vitali Klitschko in the first place, saying that they do it despite his decision to withdraw.

In addition, during the expert poll, respondents answered 4 questions in regard of front-runners of the race: the presence of the European way of thinking and political culture; experience in the field of the European integration; ability to implement the Association Agreement; use of unfair election campaign tools by the candidate.

As for the Institute of World Policy’s study, the following parameters were considered:

• the knowledge of foreign languages;

• the candidate’s consistent political support for the European integration;

• the concreteness concerning the conduction of European reforms in the 2014 campaign;

• openness and willingness to cooperate with civil society.

The total score has proven a winner — Petro Poroshenko, with the result of 10.83 points, took the first place. He has turned out to be a leader in all categories except one — concerning the fairness of the election, in which he is inferior to Anatoliy Grytsenko and Olga Bogomolets (in this category, experts estimated the amount of “black PR” and other unfair methods of campaigning).

Anatoliy Grytsenko is in second place (7,76). He is second according to most estimation parameters.

Yulia Tymoshenko and Olga Bogomolets have jostled for the third position. On the side of the first one, there are her experience and professional election program (in terms of understanding of European integration processes).

At the same time, in other nominations, the ex-Prime Minister has scored significantly less than her rival. Experts believe that Tymoshenko resorts to black PR and that she has non-European “way of thinking, political culture and behaviour” (for this indicator Tymoshenko has got -0.38 points, and Bogomolets +0.82).

Finally, the ignorance of European languages does the former Prime Minister no good. This essentially limits capacities of a politician at the European stage and reduces the efficiency of international negotiations (because a large part of meetings is spent on translation)

As a result, Tymoshenko has taken only fourth place with a score of 4.05 points, and Olga Bogomolets has finished third (5.14).

Petro Symonenko has, predictably, become the anti-leader of the ranking (-4.79 points), though Mykhailo Dobkin is not too far behind (-4.24).

PETRO POROSHENKO

Self-nominated, no party affiliation.

{1}

Based on the results of the expert survey, Petro Poroshenko is the leader of the “European president” ranking. The margin between him and the politicians, who finished 2nd-3rd in the ranking, is so great that we can talk about almost unanimous choice of the expert community. However, this does not mean that the independent experts on Ukraine’s European integration have no complaints against the candidate.

Poroshenko has been a consistent advocate of Ukraine’s European integration throughout the studied period (since 2004). He is one of the few candidates who did not change pro-European rhetoric during that time. In addition, the candidate’s fluent English and significant experience in the positions that are closely related to the European integration, in particular, as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Economic Development and Trade, contributed to Poroshenko’s victory.

However, Poroshenko’s work in the government under President Viktor Yanukovych serves both for his advantages and disadvantages. The Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, under his leadership, initiated several government decisions that exacerbated the crisis of confidence between the EU and Ukraine; not only political but also economic obstacles to the signing of the Agreement have emerged for the first time. It includes the start of the reconsideration of the conditions of Ukraine’s membership in the WTO and introduction of a scrappage duty on cars, which violates WTO rules.

Furthermore, it is in Poroshenko’s case, compared with other candidates, the issue of conflict of interest regarding business-power is the most critical. It is obvious that the candidate understands this as well, as he has promised to sell his business.

Poroshenko’s public rhetoric, parliamentary and social activities describe him as a “European candidate”.

ELECTION PROGRAM

Poroshenko’s program has become a leader with the number of its references to the European vector. The abbreviation “EU” is used six times, the word “Europe”, “European” and their derivatives — six times, the word “Euromaidan” — once. Several mentions of Europe concern the experience of transformation or EU countries’ standards; there are also parts that relate to the reforms expected in Ukraine.

In the political part, the candidate declares plans to initiate negotiations on the accession to the EU: “By the end of my term I hope to obtain the necessary political decisions from the EU to start negotiations on Ukraine’s full membership in the European Union.” This goal is quite upbeat, but in theory, with a fortuitous concourse of circumstances, can be realized. However, Poroshenko also makes quite optimistic promises, in particular, the beginning of a visa free regime introduction with the EU during the first year of his presidency (before the summer 2015).

In the economic part the candidate promises “to sign the economic part of the Agreement (the Association Agreement — IWP) with the EU as soon as possible and, in a very short time, implement its provisions, which are, indeed, a holistic plan of economic reforms in Ukraine”.

It also includes other reforms needed for Ukraine’s rapprochement with the EU, in particular, the reform of the judicial system. The need to fight corruption is mentioned three times.

ACTIVITY OVER THE LAST 10 YEARS

The IWP has studied the positions of Deputies of the seventh convocation using a selection of 2013-2014 voting results.

The candidate did not vote for the “dictatorial laws” on January 16. Not all significant decisions of the Verkhovna Rada concerning support of the European integration were voted by Poroshenko, as he was often absent from meetings of the Verkhovna Rada. Meanwhile, in the IWP’s test sample there is no voting on European issues, when Mr. Poroshenko was registered in the session hall, but did not press the button “yes”.

For the 2012 parliamentary election campaign, Poroshenko also stood with pro-European slogans. “The sovereignty of Ukraine and European integration are related, if not identical, concepts,” — he said in his program at that time.

Poroshenko is probably the most professional “Euro-integrator” among all participants of the current election race; the expert survey awarded him with the first place for experience. In 2009-2010, for five months, he served as Minister of Foreign Affairs, in 2012, for eight months — as Minister of Economic Development and Trade (in particular, Ukraine’s trade relations with European countries were in his jurisdiction). Since the end of 2012, he is a member of the parliamentary committee for European integration, from the middle of 2013 – a Co-Chair of the Parliamentary Committee for EU-Ukraine cooperation.

His work at the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade added some negative points to Poroshenko’s image as a European candidate. At the initiative of his ministry, a scrappage duty on imported cars was introduced, which violates WTO rules and Ukraine’s commitments in the framework of the Association Agreement. There were allegations that the introduction of such a duty is profitable for Poroshenko’s automotive companies. Also, during his work in the position of the Minister, Ukraine announced its intention to reconsider its WTO commitments on 371 tariff lines (although, the talks have not moved on to specifics). Both initiatives were perceived with animosity in Brussels and led to a new crisis in relations with Kyiv.

Poroshenko made no secret that he often mediated between Euro-optimists and Euro-skeptics, both at the international and domestic levels. These initiatives were not always successful. For example, in December 2013, before Viktor Yanukovych’s visit to Moscow, Poroshenko flew to Brussels. According to public reports, that visit gave the impression that he set a goal to convince European leaders that President Yanukovych preserved the European vector in his policy. “According to our information, the issues that would preclude the Association Agreement from signing have been removed from Yanukovych’s visit program,” — he stated. However, a few days later, Poroshenko harshly criticized Yanukovych on the results of his visit.

In 2013, Poroshenko constantly tried to persuade the authorities of the need to sign the agreement with the EU, arguing that otherwise the “political, economic and social consequences will be devastating”.

Petro Poroshenko did not avoid the Ukrainian politicians’ traditional problem of populist statements, which create too high expectations in the society. In late 2009, the Minister Poroshenko claimed that he expected the signing of the Association Agreement with the EU already in 2010. “By the way, we optimistically expect it to happen already in the first half of 2010,” — he added. At that time all the experts were aware that Ukraine would experience more than a year of negotiations and, after, a long process of preparing the document for signing.

EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS

He is fluent in English and Romanian. He has a wide range of contacts in the European political scene. He possesses extensive experience in positions related to the European integration. He has a great experience of negotiating with the EU officials, and according to this criterion Poroshenko is slightly inferior only to Yulia Tymoshenko.

He has a degree in international relations and international law. He has friendly relationships established over the years with leaders of some European countries.

ANATOLIY GRYTSENKO

Nominated by the “Civil Position” party

{2}

Anatoliy Grytsenko considers himself a pro-European candidate and, in conversations with reporters, argues that he had the same attitude throughout the period of his political activity. However, the analysis of the candidate’s statements in the past suggests that, several years ago in public, he had quite a moderate stand on the issue of convergence with the EU.

Grytsenko has sufficient knowledge and understanding of the European integration processes, has contacts in the West and is fluent in English. However, his political activity has always focused on the Euro-Atlantic integration rather than the European one. Probably, this has an impact on his stand. It is quite remarkable that he devoted a significant part of his presidential election program to security issues, but there is no single sentence about Ukraine’s European integration.

Meanwhile, the expert community supports some professional qualities and principles of the candidate (for example, the rejection to use dirty technologies). Experts in the field of European integration remind that, despite periods of euro-scepticism, Grytsenko has never supported the eastern course for integration. Therefore, the results of the expert survey allowed him to take the second place in the “European candidate” ranking.

ELECTION PROGRAM

Anatoliy Grytsenko’s election program radically differs from programs of all other presidential campaign front-runners. He is the only one who started that document with a sentence that claims “voters do not need programs”. A major part of the program is devoted to the description of the personal qualities of the candidate that, in his opinion, distinguish him from other participants of the election race.

Meanwhile, the document also includes program provisions that the candidate considers of the most current importance. They include the security policy, economy, fighting corruption (it is mentioned twice), reform of courts, but there are no references to the European integration. The word “Europe” is used only once in a geographical context.

However, it is not correct to say that Anatoliy Grytsenko stands for the 2014 election with no European slogans. He claims that if elected to the presidency he will implement the program of “Civil Position” party, and this one contains a foreign policy part and declares “the invariability of Ukraine’s strategic course towards European integration”.

ACTIVITY IN THE PAST

The IWP has studied the positions of Deputies of the seventh convocation using a selection of 2013-2014 voting results.

In the parliament of the current and previous convocations, Grytsenko consistently has been supporting pro-European initiatives and has not been voting for anti-European ones. He did not support the “dictatorial laws” on January 16. The candidate is a long-time supporter of the principle of personal voting; probably because of that only half of decisions of the Verkhovna Rada in the IWP test sample are supported by his vote — during other votings his card was not registered in the session hall.

In the last years of the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, Anatoliy Grytsenko demonstrated clear support for the European vector and lobbied the European Association Agreement, calling on the EU to unconditionally sign this document, despite the democracy problems in the country. “The Agreement meets long-term strategic interests of the EU and Ukraine”, — he urged in the autumn of 2013. In parliamentary elections, in 2012 he was in the list of “Batkivshchyna” party, which program also declared its support for the “European choice” and “European future”.

However, Anatoliy Grytsenko did not always share Euro-optimism views. His program in the 2010 presidential election contained no mention of European integration. Moreover, four years before the candidate Grytsenko promised in his program to reintroduce the visa regime for EU citizens if the EU does not open its borders to Ukrainians. In his public speeches, in 2009, he also talked about the need to renew the visa regime. This approach was quite popular and perhaps added some points in the election race, but it did not contribute to further rapprochement between Ukraine and the EU. Experts on the topic of visas stressed at that time that the calls for the reintroduction of the full scale visa regime with the EU are populist, and in practice this step would paralyze the work of Ukrainian diplomatic missions abroad.

The politician made skeptical statements in the regard of the European prospects and demanded “to get the respect of Europe” after the presidential election, as well. “Ukraine today has above all to learn to respect itself and to do not seek to appear in the European Union or NATO as soon as possible. If now the EU was ready to accept us, I would rather say no than yes,” — he argued in the spring of 2010.

EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS

Considering his educational and professional level, Anatoliy Grytsenko fully conforms to the requirements for a “European president”. He is fluent in English. He has a degree; he studied in Ukraine and the USA. He was the head of the Analytical Service of the National Security Council and the Razumkov Centre for Economic and Political Studies.

He has extensive experience in negotiations with European politicians and officials. He is a recognized expert in defence and Euro-Atlantic integration issues. However, the candidate has no experience in posts that are directly related to European integration.

OLGA BOGOMOLETS

Self-nominated, no party affiliation.

{3}

During the election campaign, she positions herself as a pro-European candidate, but she avoids details on Ukraine’s European aspirations. Her election program is a vivid illustration of this.

This vague approach is consistent with the candidate’s experience. Ms. Bogomolets has never dealt with the European integration and, obviously, she is not aware of the details of the process. However, at the level of values, she may call herself a pro-European politician and public figure.

Experts confirm this. They have recognized that Olga Bogomolets lacks expertise. However, they have given her the third place in the ranking.

ELECTION PROGRAM

The candidate Olga Bogomolets promises a “pro-European integration foreign policy” if elected to the presidency, but she does not focus on this issue. Thus, the word “European” and its derivational forms are used only twice in the candidate’s program.

The candidate Bogomolets is one of the few race runners who mention in the program that “European integration — it is not only external but also internal politics.” Meanwhile, this very proper motto is not disclosed in the text of the program. This gives a reason to assume that the candidate lacks understanding of the essentials and content of European reform. This gap can be eliminated if there are specialists on the European integration in the candidate’s team.

From among the few particular “European” directions, which are stated in the document, it is worth highlighting a reference to elements of “good governance”: an increase of “civil society’s influence on the government”, an introduction of “electronic government”, “electronic democracy”. The program also mentions fighting corruption several times.

Meanwhile, her program contains no or almost no evident populist slogans and tasks that are a priori impossible of fulfilment; this enhances its compliance with the “European candidate” status.

ACTIVITY OVER THE LAST 10 YEARS

Olga Bogomolets is a newcomer to politics, though, in 2006-2008, she gained some political experience as a Deputy in the Kyiv City Council. This period is not to the candidate’s advantage, since shortly after the election she withdrew from the faction “Our Ukraine”, by the list of which she was elected, and began to work with the team of the then Mayor Leonid Chernovetskyi.

In early elections to the Kyiv City Council in 2008, she was the only turncoat deputy who was once again put on the list of “Our Ukraine”, but the party failed to cross the electoral threshold (it received only 2%).

The experience of Olga Bogomolets in the public sector is much more positive. She is well known as a philanthropist, the head of public initiatives in medical, historical, cultural spheres; she is also known as a fighter of illegal construction.

Her activities during the Euromaidan and before its start are, undoubtedly, a positive stage. In the spring of 2013 in her letters, she called on the authorities to fulfil the EU’s requirements for signing the agreement. In November of 2013, she called on medical students to support Euromaidan. She contributed to the establishment of the Maidan’s medical service after the first cases of violence, and, eventually, became one of its informal leaders.

EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS

With the exception of the experience in the field of European integration (after all, one can talk about the complete lack thereof), the candidate Olga Bogomolets meets all the educational requirements for a European president.

She speaks English. She has two degrees — in medicine (1989) and pedagogy (2001); a degree of Doctor of Medicine. In 1993-1994, she studied at the Pennsylvania Medical University and the Bernard Ackerman Institute for Dermatopathology (Philadelphia, USA).

She has never visited Brussels for political purposes, because she did not deal with politics and European integration; we only know about her trips to European capitals to participate in activities of the medical community.

Her experience in negotiations with European politicians and officials is slight and not always positive. Thus, in late February Olga Bogomolets met with Foreign Minister Urmas Paet during his visit to Ukraine. Soon, an intercepted conversation of Paet with the EU’s foreign policy chief, Catherine Ashton, in which the Minister retold the details of his conversation with Bogomolets (in particular, the assumption that opposition leaders ordered the killing of protesters), was “leaked” to the Internet. Later Bogomolets said that she was misunderstood and that she did not tell Paet those details that he referred to.

YULIA TYMOSHENKO

Nominated by the party “Batkivshchyna”

{4}

In all election campaigns over the past 10 years, in which Tymoshenko took part, she positioned herself as a pro-European candidate.

However, Yulia Tymoshenko’s performance in high government positions in the field of the European integration gives a reason to experts for a discussion. It is believed that while being the head of the government Ms. Tymoshenko did not make necessary efforts to fulfill commitments to the EU and European reforms were not carried out. However, there is also an opposite opinion — after all, other politicians who served as Ukraine’s Prime Minister, also did not succeed significantly in this area. In addition, over the past 10 years, there was a position of Vice Prime Minister for European Integration only in Tymoshenko’s governments. There are also opposing views concerning her influence on the signing of the Association Agreement: there were signals that she contributed to the signing of the document, and that she, also, blocked it.

In any case, Yulia Tymoshenko is running again with European slogans now. She is the undisputed leader concerning contacts in the West and political negotiations experience. However, the candidate’s disadvantage is her ignorance of foreign languages, which significantly limits the circle of partners with whom tete-a- tete negotiations would be possible.

ELECTION PROGRAM.

Yulia Tymoshenko’s program is largely pro-European. The abbreviation “EU” and conjugations of the word “Europe” are used in the seven times. The candidate sets specific and, mostly, correct objectives: ”to sign the Association Agreement in full by the end of 2014”; “to establish a mechanism for coordination of the European integration policy” (this, by the way, is a long-standing requirement of an expert community to the country’s government); “to achieve EU membership as soon as possible”. The time limit for the expected accession to the EU is not specified, which is right in terms of fairness of the program.

However, not all “European” norms of the document can be called honest and professional. Yulia Tymoshenko promises to sign the Association Agreement by the end of the year “including a free trade zone and visa-free regime for Ukraine’s citizens”, while, in fact, this agreement has nothing to do with the abolition of visas. By the way, the future introduction of a visa-free regime will not require signing of any agreement between Ukraine and the EU because it is a unilateral decision of Brussels.

It is difficult to say why this provision has been included in the program — either due to a lack of knowledge of European affairs or as a manipulation attempt.

The program includes a number of provisions related to European reforms. In addition to the promise to create a government mechanism for coordination of the European integration (Tymoshenko, by the way, is the only candidate from among the front-runners who made this important promise), the document refers to the ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and to reforms in the area of good governance: a reform of administrative services, the introduction of e-governance and workflow.

ACTIVITY OVER THE PAST PERIOD

From 2011, Yulia Tymoshenko, due to conditions beyond her control, was pushed away from active political life. Nevertheless, her position, expressed in letters, through associates and international mediators, has had a significant impact on events.

Experts on European integration remember the years of Tymoshenko’s imprisonment as a period of mutually exclusive signals sent by the leader of the party “Batkivshchyna” to the EU.

In her statements to the press and public letters, Yulia Tymoshenko has consistently stated that she supports the conclusion of the Association Agreement despite the existence of problems of democracy. “Although I know that my release is a condition for the signing, I ask to sign the Agreement in any case,” — she said in her letter in November 2011. “Being in prison and realizing that the regime has nothing to do with Europe and democracy, I ask, nevertheless, to initial the Agreement” (March 2012). “We have to release not only political prisoners, we should liberate Ukraine. It means we must certainly sign the Agreement” (November 2013).

However, the politicians, who talked to her while in custody, sent an opposite signal at public events and confidential meetings — about the inadmissibility of the signing of the Association Agreement with the European Union under Yanukovych. “The agreement should not be signed and ratified when opposition leaders are in jail”, — Tymoshenko’s adviser Hryhoriy Nemyria, insisted at the EPP Summit in March 2012. The Vice President of the European Parliament, Jacek Protasevich, received a similar message after a meeting with Yulia Tymoshenko in May 2012: “She believes that the European policy must be firm, including freezing the process of signing and ratifying the Agreement”.

For the 2010 presidential race, Tymoshenko stood with pro-European slogans. “Ukraine will become a member of the European Union,” — she promised in her election program. “I set an objective to sign the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU during the first year“, — the candidate declared in January 2010.

It is worth adding that the Prime Minister Tymoshenko did not avoid a traditional Ukrainian leaders’ disease of inflated expectations in relations with the EU. She (as well as the then President Yushchenko) gave many promises that technically could not be fulfilled; this caused misunderstanding and irritation in Brussels. “By the end of 2009, at the latest, in the beginning of the next year, we will have the Association Agreement signed”, — she said in July 2009. As everybody knows, the negotiations on the Agreement were completed only in the end of 2011, while over the years of Yushchenko-Tymoshenko’s leadership the progress in the negotiations was rather frugal.

Tymoshenko’s older election programs (in the parliamentary elections of 2006 and 2007), there were no references to the European integration, but the candidate had claimed the European future for the country already before. “Ukraine’s way to the EU is confident and consistent, Ukraine will do anything for it,” — she said in the summer of 2005.

Among the public positions, in which Yulia Tymoshenko served, the position of Prime Minister (2005, 2007-2010) was related to the European integration. There was the Vice Prime Minister for European integration in the Cabinet of Ministers in both periods of her service. The Coordination Bureau for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration was created in 2008 (abolished in 2010). However, Tymoshenko’s governments had little success in conducting real European reforms; this gave a reason for the constant criticism from Brussels.

EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS

She has two degrees in economics (1984, 1999), and Ph.D. in economics. She does not speak EU languages, in particular, English. Nevertheless, Tymoshenko, among all participants of the race, has the most significant experience in international negotiations (acquired in the position of the Prime Minister). She is personally acquainted with many top officials of the European Union and European countries.

She has experience in a position related to the European integration, as the head of government. Meanwhile, expert evaluations of the quality of her work in this position regarding the pro-European course are rather ambiguous.

Full version of the study is here.

Comments theme

Comments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments themeComments.